PR181

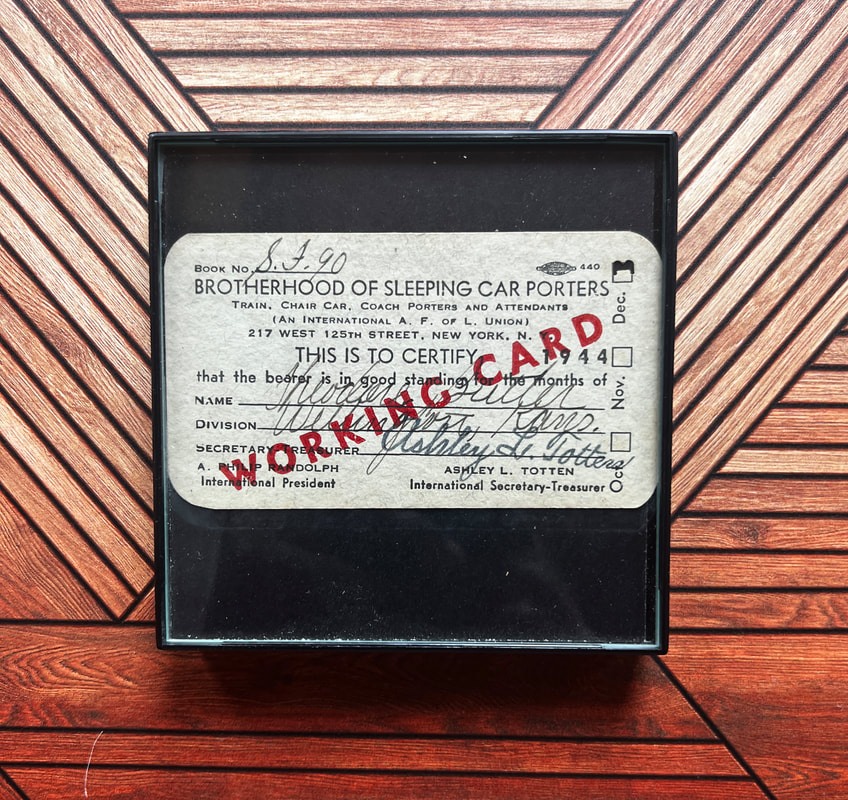

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

1944 Working Card

They got their name from George Pullman, who started a train company in the 1860s providing sleeping cars and luxury travel in America. His Pullman Palace Car Company founded in Chicago hired thousands of African-American men (many being former slaves) some years after the Civil War to serve White passengers traveling across the country on its luxury railroad sleeping cars.Even though they were overworked and underpaid and faced racism on the job, the Pullman porters would help create a new Black middle class and launch the civil rights movement besides helping fuel the Great Migration. This is their story.

Railroads expanded in 1859 inspiring Pullman to convert two old passenger cars into new and improved sleepers with permission from authorities. He then hired White people to work as conductors and Blacks, mostly former slaves from the South, to be porters. As porters, their roles included serving food and beverages, cleaning the rail cars, carrying luggage, shining shoes, and so on.

Pullman had a reason for hiring only Black men or dark-skinned former slaves to do these jobs. “His reasoning was twofold. One it was that they would come and work for him for whatever price, however low the price he decided to pay them, and he paid them next to nothing, and that they would work as long and as hard as he would demand of them, and he demanded them working 100 or more hours a week, author Larry Tye told NPR.

“But the more interesting reason that he hired them was he was trying to sell railroad customers back then on a whole new concept, on the concept of overnight travel. And his sleeping cars were more than double the price of a conventional railroad ticket.

“So he had to convince these passengers that they were going to get such ultimate service, such luxurious service, that it was worth paying this, what seemed like an extremely high fee. And who better to convince them that they were going to be waited on brilliantly than ex-slaves, who embodied for these white passengers the whole notion of service.”

What’s more, Pullman “knew they [black porters] would come cheap, and he paid them next to nothing. And he knew that there was never a question off the train that you would be embarrassed by running into one of these Pullman porters and having them remember something you did that you didn’t want your wife or husband, perhaps, to remember during that long trip,” Tye said.

As Pullman’s cars were used on long-distance train routes that could last from a few hours to entire days, Pullman porters worked long hours, usually 400 hours a month, and did not have much time off. Despite this, many Black Americans envied their job and hoped to be Pullman porters to raise their status. Reports say that in 1926 Pullman porters made around $810 per year (about $12,000 today), which was much more than the median Black worker at the time. This made them one of the most influential Black men in America years following the Civil War.

Still, Pullman porters were among the worst-paid of all train employees. But as time went on, they combined their poor salaries with tips, saved enough money, and sent their children and grandchildren to college, which helped them reach middle-class status. (Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, Olympic track star Wilma Rudolph, and former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown were descendants of Pullman porters).

And in 1925, years after enduring racism and discrimination at work, the porters finally organized and became the first African-American labor union. The American Railway Union had at the time organized most Pullman employees but declined to include Black workers, including porters. So the porters formed the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) to protest this and other matters. A. Philip Randolph helped the porters fight for and win a collective bargaining agreement in 1937 — the first-ever agreement between a union of Black workers and a major U.S. company.

Besides getting increased wages for porters, the agreement set a limit of 240 working hours a month, according to History. Randolph would later help organize the civil rights movement. E.D. Nixon, who was a Pullman porter and leader of a local chapter of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, worked with one of his employees to help start the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama. In 1969, the Pullman Company ended its sleeping car service as passenger train service declined and the civil rights movement grew.

Railroads expanded in 1859 inspiring Pullman to convert two old passenger cars into new and improved sleepers with permission from authorities. He then hired White people to work as conductors and Blacks, mostly former slaves from the South, to be porters. As porters, their roles included serving food and beverages, cleaning the rail cars, carrying luggage, shining shoes, and so on.

Pullman had a reason for hiring only Black men or dark-skinned former slaves to do these jobs. “His reasoning was twofold. One it was that they would come and work for him for whatever price, however low the price he decided to pay them, and he paid them next to nothing, and that they would work as long and as hard as he would demand of them, and he demanded them working 100 or more hours a week, author Larry Tye told NPR.

“But the more interesting reason that he hired them was he was trying to sell railroad customers back then on a whole new concept, on the concept of overnight travel. And his sleeping cars were more than double the price of a conventional railroad ticket.

“So he had to convince these passengers that they were going to get such ultimate service, such luxurious service, that it was worth paying this, what seemed like an extremely high fee. And who better to convince them that they were going to be waited on brilliantly than ex-slaves, who embodied for these white passengers the whole notion of service.”

What’s more, Pullman “knew they [black porters] would come cheap, and he paid them next to nothing. And he knew that there was never a question off the train that you would be embarrassed by running into one of these Pullman porters and having them remember something you did that you didn’t want your wife or husband, perhaps, to remember during that long trip,” Tye said.

As Pullman’s cars were used on long-distance train routes that could last from a few hours to entire days, Pullman porters worked long hours, usually 400 hours a month, and did not have much time off. Despite this, many Black Americans envied their job and hoped to be Pullman porters to raise their status. Reports say that in 1926 Pullman porters made around $810 per year (about $12,000 today), which was much more than the median Black worker at the time. This made them one of the most influential Black men in America years following the Civil War.

Still, Pullman porters were among the worst-paid of all train employees. But as time went on, they combined their poor salaries with tips, saved enough money, and sent their children and grandchildren to college, which helped them reach middle-class status. (Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, Olympic track star Wilma Rudolph, and former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown were descendants of Pullman porters).

And in 1925, years after enduring racism and discrimination at work, the porters finally organized and became the first African-American labor union. The American Railway Union had at the time organized most Pullman employees but declined to include Black workers, including porters. So the porters formed the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) to protest this and other matters. A. Philip Randolph helped the porters fight for and win a collective bargaining agreement in 1937 — the first-ever agreement between a union of Black workers and a major U.S. company.

Besides getting increased wages for porters, the agreement set a limit of 240 working hours a month, according to History. Randolph would later help organize the civil rights movement. E.D. Nixon, who was a Pullman porter and leader of a local chapter of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, worked with one of his employees to help start the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama. In 1969, the Pullman Company ended its sleeping car service as passenger train service declined and the civil rights movement grew.