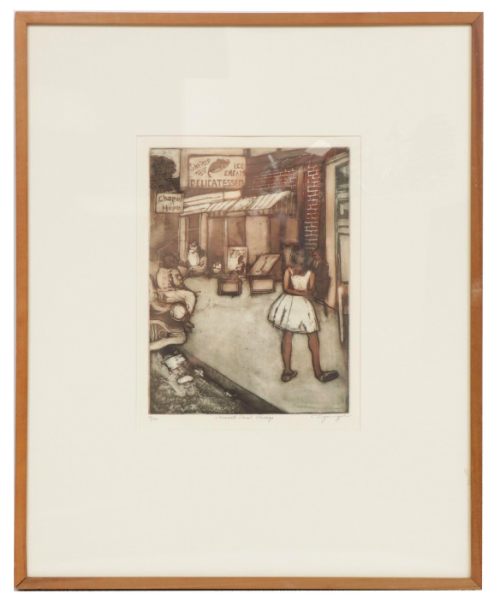

A169

Susan Dyasigner - “Maxwell Street - Chicago”

Susan Dysinger

Maxwell Street, Chicago - Aquatint etching on paper

Signed to the lower right, Numbered 17/100

Maxwell Street, Chicago - Aquatint etching on paper

Signed to the lower right, Numbered 17/100

In the 1930s and 1940s, when many black musicians came to Chicago from the segregated South, they brought with them outdoor music. But when the early blues musicians began playing outside on Maxwell Street – the place where they could be heard by the greatest number of people – they realized they needed either a louder than standard Resonator guitar or amplifiers and electrical instruments in order to be heard. Over several decades, the use of these new instruments, and the interaction between established city musicians such as Big Bill Broonzy and new arrivals from the South, produced a new musical genre – electrified, urban blues, later coined, "Chicago Blues."

This amplified, new sound was different from the acoustic country blues played in the South. It was popularized by blues giants such as Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Bo Diddley and Howlin' Wolf and evolved into rock & roll. From the first, the blues signified a lament or elegy for hard times, though it outgrew that limitation. When economic decline in the American South after World War I caused many Delta Blues and Jazz musicians - notably Louis Armstrong – to migrate north to Chicago, the first economically secure class willing to help them was the mostly Jewish merchants of the area around Maxwell Street, who by that time were able to rent or own store buildings. These merchants encouraged blues players to set up near their storefronts and provided them with electric extension cords to run the new high-tech instruments.

Shoppers lured by the chance to hear blues music could be grabbed and hauled into the store where they were sold a suit of clothes, shoes, etc. One of the regular performers was the self-styled Maxwell Street Jimmy Davis, who played in the area for over 40 years. The last blues performances on Maxwell Street occurred in 1999-2000, on a bandstand erected by Frank "Little Sonny" Scott, Jr., near the north-east corner of Maxwell and Halsted Streets, on land recently vacated by the demolition of a historic building. The extension cord ran from the last remaining building in use, the Maxworks Cooperative headquarters, 300 feet (91 m) east, at 716 Maxwell Street.

This amplified, new sound was different from the acoustic country blues played in the South. It was popularized by blues giants such as Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Bo Diddley and Howlin' Wolf and evolved into rock & roll. From the first, the blues signified a lament or elegy for hard times, though it outgrew that limitation. When economic decline in the American South after World War I caused many Delta Blues and Jazz musicians - notably Louis Armstrong – to migrate north to Chicago, the first economically secure class willing to help them was the mostly Jewish merchants of the area around Maxwell Street, who by that time were able to rent or own store buildings. These merchants encouraged blues players to set up near their storefronts and provided them with electric extension cords to run the new high-tech instruments.

Shoppers lured by the chance to hear blues music could be grabbed and hauled into the store where they were sold a suit of clothes, shoes, etc. One of the regular performers was the self-styled Maxwell Street Jimmy Davis, who played in the area for over 40 years. The last blues performances on Maxwell Street occurred in 1999-2000, on a bandstand erected by Frank "Little Sonny" Scott, Jr., near the north-east corner of Maxwell and Halsted Streets, on land recently vacated by the demolition of a historic building. The extension cord ran from the last remaining building in use, the Maxworks Cooperative headquarters, 300 feet (91 m) east, at 716 Maxwell Street.